A Better Society

One of the things I worry about while doing my research is how to drive it towards building a better society. Although the concept of a better society may differ from one culture to the other, I believe any society gets better whenever all of its members experience more freedom to enjoy their rights.

Among the untold manners technology can be used to breach people’s rights, five flaws in the way we are doing informatics get my attention. Devices and programs usually suffer from (1) lack of safety, (2) lack of trustworthiness, (3) lack of privacy, (4) ignorance of diversity, and (5) lack of accountability. Not unintentionally, the projects I’ve been contributing to in the past few years tackle one or more of these issues.

Safety

From the many ways safety can be harmed by technology, the improper dissemination of sensitive content (such as pornography or violence), to inadequate audiences (such as kids or unwary spectators), gained my attention while I was developing my PhD, under the supervision of prof. Anderson Rocha (who generously proposed the topic).

With the popularity and pervasiveness of online video streams, sensitive scenes depicting suicide, murder, and even rape have been broadcasted on the Internet, raising questions about the safety of these services. Aware of this situation, Samsung has funded us to focus on the development of solutions to detect sensitive video. Rather than aiming at denouncing or morally condemning the lawful consumers of certain types of sensitive content, our intent has always been to support the implementation of filtering and warning features that would make player systems safer (especially in the case of child spectators).

I’ve had the chance to tackle the lack of safety in video streaming systems through the SMA project.

Trustworthiness

In the era of misinformation and fake news, there is a symptomatic undermining of trust not only in textual but also in visual information. People are conscious of the existence of image editing software (e.g., Photoshop), with which even unskilled users can easily fabricate and manipulate pictures. Although many of these manipulations have benign purposes (no, there is nothing wrong with your memes), some contents are generated with malicious intents, such as general public deception and propaganda.

The lack of available solutions to assess the integrity of images and videos allows adversarial manipulated data to have a negative impact on the way people relate to each other on the Internet. They don’t know what to believe or whom to trust anymore. In addition, fraudulent images represent a challenge even for the scientific community. Aware of this scenario, DARPA has been funding us, at CVRL, to conduct research on the development of tools to verify the integrity of digital images.

I’m having the chance to tackle the lack of trustworthiness in visual media systems through the MediFor and Sci-Int projects.

Privacy and Diversity

With the advent of deep learning and the necessity for large datasets, visual data collection has become an important step of Computer Vision and Machine Learning research. Due to the popularity of image and video capture devices (such as digital cameras, smartphones, dash cams, etc.), large datasets can now be quickly generated. Nevertheless, a major question that stands out in such a process is how to protect the privacy of people who are eventually being recorded. Imagine, for example, a dash cam that is collecting road data for a self-driving car project. In a major city, plenty of people will certainly be captured in the footages, and it is very unlikely that one will be able to obtain image rights for each individual.

Interested in such issue, we, at CVRL, investigate the generation of realistic synthetic faces, whose identities do not belong to a real existing person, hence avoiding privacy breaches. The idea is to de-identify the recorded individuals, by replacing their faces with synthetic assets.

In addition, collected data may be biased, due to a lack of diversity in the captured individuals. Consider, for instance, training video footages collected in China. It is very unlikely that black people will be represented in such a dataset.

Limitations of this nature comprise what I call ignorance of diversity and are the potential cause of many technological failures in the presence of underrepresented groups. Unfortunately, glitches like these may go beyond the technological aspects and prejudice the rights of equality in face of diversity. To cope with this problem, similar to the privacy protection strategy, synthetic identities can be used to diversify the recorded individuals by performing face replacement, providing controlled variation of not only ethnicity but also of age and of gender.

I’m having the chance to tackle the lack of privacy and ignorance of diversity in image and video datasets through the SREFV project.

Accountability

People have the right to understand in details the decisions made about them by algorithms belonging to either government or industry. This is fundamental to give them the possibility of questioning determinations and defending against resolutions that might be the outcome of incorrect, rigged, or even bogus computations. In this context, accountability becomes a relevant concept, since it comprises the property of an automated decision system to be fair, transparent, and explainable to human beings. As a consequence, the more accountable a system is, the more audit power it gives to people.

Within the field of Biometrics, traditional iris recognition solutions are well known for constituting very reliable methods of identity verification. Nevertheless, since they are not human-friendly enough to convince people who do not possess image processing expertise, their usage before a jury in courts of law is usually avoided. Aware of this limitation, Prof. Adam Czajka has started at CVRL the investigation of human-intelligible iris matching strategies.

I’m having the chance to tackle the lack of accountability in iris recognition algorithms through the TSHEPII project.

Keep pushing

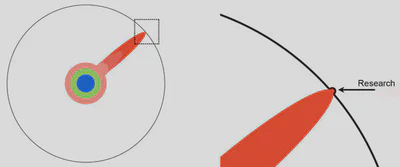

Although the aforementioned efforts may seem minuscule in face of the size of the challenge of building a better society, I try to calm myself down by making a parallel to the explanation of Prof. Matt Might on how the human knowledge increases with the progress of scientific research. As he advises, I keep pushing.